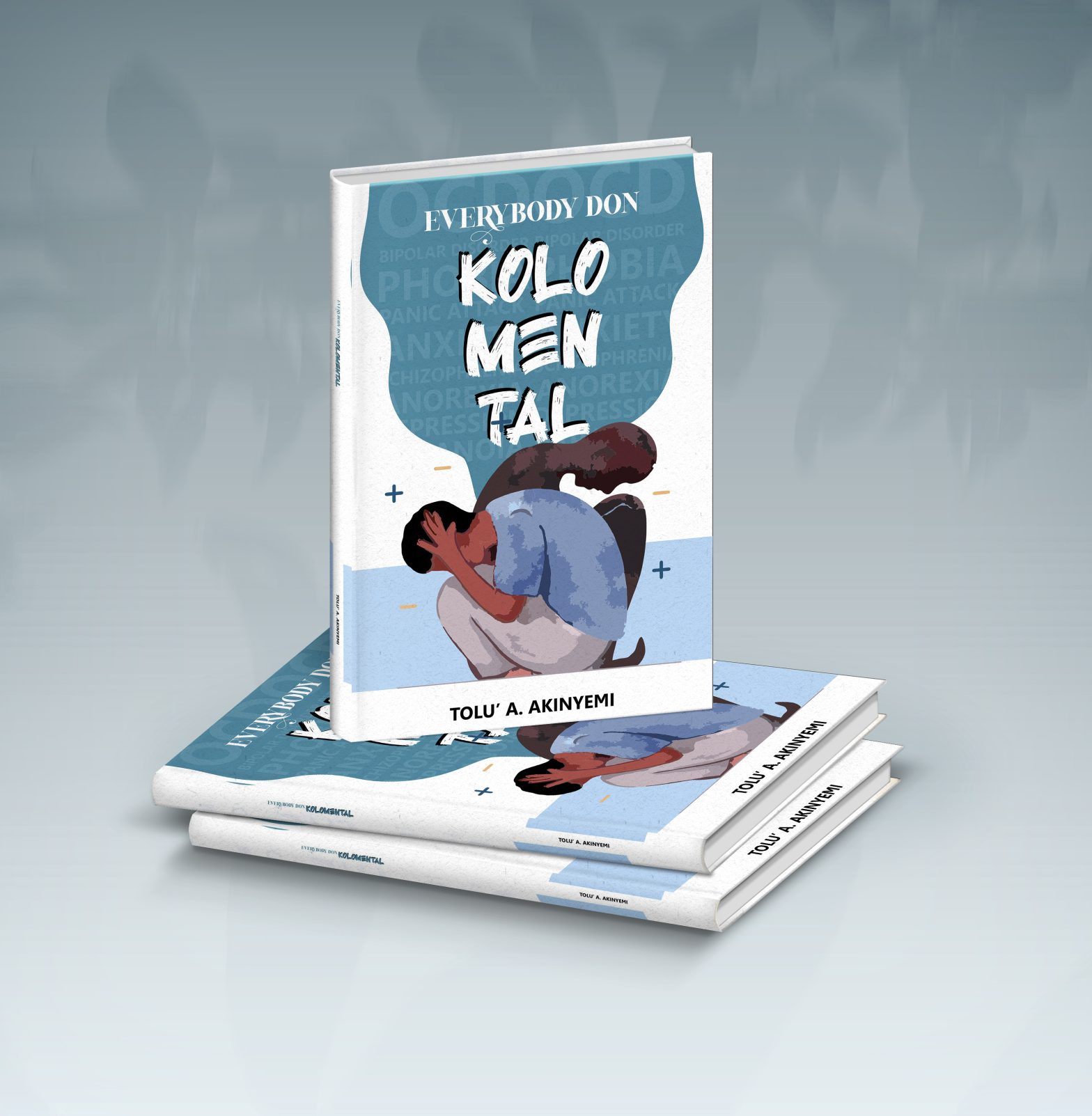

Title: EVERYBODY DON KOLOMENTAL

Genre: Poetry (a collection)

Author: Tolu’ A. Akinyemi

Publisher: The Roaring Lion Newcastle LTD

Reviewer: ENANG, God’swill Effiong

Year of Publication: 2021

Word Count: 1,353

Injustice, Trauma And Death: Knotted Ropes In Tolu’ A. Akinyemi’s Everybody Don Kolomental

‘Life is a jest; and all things show it.

I thought so once; but now I know it.’

John Gay (‘My Own Epitaph’)

The world right now is not what we expect to see. Post-modernism rubs disillusionment in all our faces. Yes! You, me and us; because everybody don kolomental. As a result, we’ll see how injustice, trauma and death have been woven into one fabric by the poet, to showing us nothingness.

Blinded by pressures of this world or because man is inherently mad, he becomes irrational in his decision makings. Akinyemi makes this loud in two poems from this collection: A Single Story and Guilty as Charged. In the former, it could be said that Akinyemi borrows the underlining message from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2009 TED Talk, The Danger of a Single Story. In Akinyemi’s poem, he personifies a single story, ‘selling false narratives like a monopoly with/no competitor.’ He tells the story of a man who was labelled a thief as the people ‘broke the news with trembling lips’ in the morning. The last two words (‘trembling lips’) from the quote implies they were quite remorseful, knowing he was not a thief (after they had exerted jungle justice on him by setting him ablaze the night before) because the ‘cries of thief, thief, thief that rended the air were a hoax.’ And the last stanza of this poem depicts that he ‘was a victim of a single story. In furtherance, how was this single story created? Like Adichie rightly put in The Danger of a Single Story: ‘…shows people [or a person, in this case] as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again and that is what they become.’ So, the dead man from the poem died because he was labelled a ‘thief’ repeatedly, and it became his danger.

Also, Guilty as Charged preaches the same theme of injustice as the preceding paragraph. The persona recalls the case of a Nigerian Entrepreneur (‘Izu’) who had ‘gone to the land of no return.’ The poet adopts a euphemistic approach to suggesting how grave their actions have been and how mildly they have painted it. Izu’s death resulted from false accusations. And why is that so? It is so because the persona says that a ‘rape allegation’ is sacrosanct. / You’re either guilty or guilty.’ And he was ‘[n]ailed to the cross. / The end.’ The Biblical allusion of Jesus Christ could mean the poet, saying that Izu was just sacrificed for a crime he didn’t commit like Jesus Christ was. All is still pinned to Adichie’s The Danger of a Single Story and according to her (since Akinyemi didn’t provide any solution, perhaps, because he believes it is almost impossible in an age like this or to envelope more pity on the reader), she proffers a solution. She says: ‘That when we reject the single story, when we realise that there is never a single story about any place [or person], we regain a kind of paradise.’

Trauma occurs when the victim is not prepared for what hits him/her or when he/she never expected to get something bad or isn’t mature to handle the unpleasant situation. When it finally occurs, then disillusionment (a sub-set of trauma) takes place. In this collection, Tolu’ Akinyemi uses almost half of the forty poems to preach the inhumane contribution to trauma, the neglect of traumatic beings and the aftermaths.

For instance, Men Don’t Cry wears a humour because men are also humans, and they do cry or should… when needed. But the poet presents it that way to tell the masses how the world expects that from men. However, during this indoctrination, I am sure they never knew that there might always be a setback to bottling up pain. The persona from the poem laments on how he cried silent, invisible tears in his room that they became a river. Of course, this is hyperbolic. He goes on to recollect, thirty years ago, when his mother said that ‘[b]oys don’t cry’. And that made him take back his tears, ‘[d]eeply’. Here, one can see that the persona suffers from neglect because he was taught as a boy while growing up that men’s pain or tears shouldn’t be shared or seen, respectively. And the effect on that to ‘Freddie’ (the persona’s friend) is that he ‘died in a pool of tears.’

In addition, Competition depicts what some Africans in diaspora go through from their parents back home. Since America and its likes are ‘lands of opportunities’ (as most Black immigrants see them), some African parents want their children overseas to literally build them heaven back home or send them the things of paradise. This becomes authentic because the poet is also an African (in short, a Nigerian) in diaspora who must have witnessed this either directly or indirectly and had taken the pain to write. In Competition, the persona is haunted by the words of his father to him, because ‘Nicole the daughter of Nzeribe sent two cars from Italy last/week.’ What are those words? You want to know? Well, the words are: ‘You’re here like matter, adding weight and/occupying space.’ It’s funny, right? But the ironic part is how he (the persona) could tell his father that ‘Nicole’s twigs are dried out…; [h]er shrubs are no longer green.’ Here, ‘twigs’ could be symbolising her growth and ‘shrubs’, her pool of wealth.

If one critically examines Nzeribe’s consciousness, one could tell that while she had nothing, she saw it as a must to always allow her parents to think things are always rosy, while they aren’t. Now, this is something Nzeribe didn’t expect; couldn’t bear (that is, trauma) until she died prematurely. Thus, Akinyemi craftily shows us the incompletely true expectation of African parents to their immigrant children without wanting to hear and accept their pains (if any), resulting (most likely) in their untimely death.

Finally, death becomes an end product of the injustice and trauma of the victims. And the poet tells this through characters who died as a result. Examples have been given in all poems used in this review. Aside from these, other examples can be drawn from the poet’s twenty-seventh poem, Public Service Announcement and his thirty-ninth, Be a Strong Man. In the former (Public Service Announcement), I must confess that the poet speaks a volume with just a few words. The persona begins with the fact that his favourite uncle’s spirit roams angrily (thereby highlighting an African belief in the supernatural). He who died at an early age (‘Left before sunset’) because of the stigma (negative words) which his peers tagged him to be, although, a ‘Harvard trained’. We were then given a comparison of two likeable quicker deaths (by fire or by being traumatised). For instance, the third stanza explains how the late uncle got addicted to smoking and got scarred by its fire but survived: ‘Burnt lips from smokes. Chronic addict. Blue chinos caught / fire from ciggies. Called the fire service, survived—never / burnt alive’. And the last stanza tells the second and quicker death: ‘The stigma was never erased. / Inadequate. Incapable. Inconsequential.’ Hence, the poet is saying that we should be mindful of what we say to people.

Be a Strong Man, depicts what a man could possibly go through domestically; that is, by a scornful wife or naturally (‘When the vicissitudes of life rained hail and / thunderstorm), and he’s still expected to bottle-up and ‘[b]e as strong as a rock’. Unfortunately, that person ‘…was a strongman until he withered away.’ What an irony.

In conclusion, since injustice, trauma and death prevail in a post-modern world like ours, meeting disappointments in science, humanity and other aspects of life is guaranteed. So, wouldn’t it be fair if we borrowed from John Gay’s couplet, used as an epigraph to this work?

I haven’t read this book, yet; but with a review like this it just feels like I read all 40 poems myself!